More of Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol

- Including a Guided Tour of Doom Patrols Past led by Mr Morrison himself.

This is a revival of a series of posts on DC’s favourite team of lovable misfits that I left off in October 2009.

We’ve already looked at the stories collected in Crawling from the Wreckage and The Painting that Ate Paris, which covered Grant's earliest Doom Patrol issues, #19-34. I hope I’ve shown that Morrison wasn’t just producing weirdness for the sake of weirdness. In Doom Patrol, he is not just stretching the kinds of stories that can be told in superhero comics, which fold very personal interests into the mix in areas like art, psychology and philosophy. In the particular case of Doom Patrol, he seems to be using these superhero comics to talk about identity and difference, as well as introducing a few new mythologies for exploring the origins of suffering, pain and dissolution in the world. He uses experimental forms and the startlingly original content of these stories to take us inside the shattered dysfunctional world of society’s outsiders. Like all good comics creators, he is showing as much as telling!

I think my approach to reviewing these comics will be a little bit different going forward from here. When I reviewed the first two Doom Patrol collections and the first Animal Man trade, I knew I liked Morrison’s comics, but not really why I liked them. I didn’t really understand what he was doing with them at all. So in the beginning, I broke them down page-by-page and sometimes panel-by-panel to try to comprehensively analyse what was going on in them. (I wrote over 1700 words – 3 Word pages– on the first 7 pages of issue #19, for instance!)

I've been pretty systematically working my way through Morrison's comics since, trying to see if I can glean any signals of information amongst what may often seem like so much white noise.

Since those far-off days, I’ve read The Invisibles and The Filth, and tried to suss out all of their meanings and philosophies, not to mention loads of other Morrison offerings like Sebastian O, and Seven Soldiers of Victory. I’ve managed to read half of both JLA and Grant’s mind-bending Batman Magnum Opus. I don’t know if anyone who has been reading along with me has been in any way enlightened, but I feel I have a grasp by now of what Grant is doing and how he gets it done. It’s been fascinating seeing how much philosophy and commentary on life and comics Grant has managed to squeeze into his work. But I don’t want to repeat myself too much going forward. If we don’t get it by now...

So I think I’ll just be skimming over most of the remaining storylines in Grant’s Doom Patrol and just pick out a few things here and there that are particularly fun or illuminating. We’ll start off with the title arc of the collection ‘Down Paradise Way’, which introduces comics first transgender public thoroughfare, and features the Men from N.O.W.H.E.R.E.

So I think I’ll just be skimming over most of the remaining storylines in Grant’s Doom Patrol and just pick out a few things here and there that are particularly fun or illuminating. We’ll start off with the title arc of the collection ‘Down Paradise Way’, which introduces comics first transgender public thoroughfare, and features the Men from N.O.W.H.E.R.E.

Replies

Doom Patrol #35-36

'Down Paradise Way'

At first glance this two-parter looks like previous story arcs where the Patrol found themselves battling terrifying abstract looking creatures who seem to follow their own inhuman logic. In this case it's the Men from N.O.W.H.E.R.E. Check them out! However, this little confrontation brings to centre stage one of the main concerns of the whole series in a way that the encounters with the similar Scissormen and Dry Batchelors didn't. The whole run examines notions of so-called 'normality' and the marginalisation of those that don't fit in, and 'Down Paradise Way' tackles this theme head on.

However, this little confrontation brings to centre stage one of the main concerns of the whole series in a way that the encounters with the similar Scissormen and Dry Batchelors didn't. The whole run examines notions of so-called 'normality' and the marginalisation of those that don't fit in, and 'Down Paradise Way' tackles this theme head on.

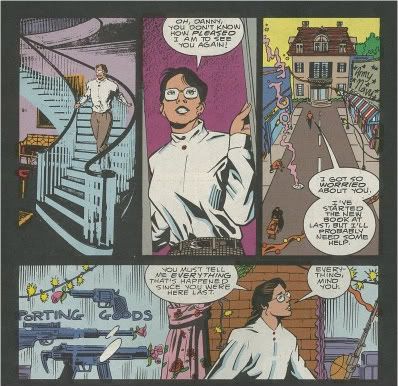

‘Normality’ is represented by Mr Jones, who lives in a nice suburban home with his wife. The exchanges between them are accompanied by a sit-com laugh track. Mr Jones has created the Men from N.O.W.H.E.R.E. to get rid of the quirks in the world and make it more 'normal'. Mr Jones hatred of difference and deviancy is thematically opposed in the story by Danny the Street, the notorious transvestite bye-road that has a warm welcome for anyone and everyone who wants to take shelter there. Danny allows and encourages everyone to be just who they are, no matter how weird, antisocial or misunderstood.

It's quite a clever juxtaposition. Jones' insistence on 'normality' leads inevitably to the eradication of those that don't measure up. Danny is tolerant and inclusive. Of course, Danny's love is no match for the violence of Jones' strange army until the Doom Patrol arrives. The Patrol don't just embody difference and 'weirdness', they fight for it.

Of course, Danny's attitude is pretty much Morrison's. Morrison's work again and again shows us the view from the other side of the window – that of those outside looking in. It's funny to realise that even Morrison's fiction embodies Danny's inclusivity. Look at his Batman run. It is all built around the notion that every Batman we've seen before now is valid, and all those adventures, no matter how different in tone from each other, or how strange, actually happened. Whilst certain Batman writers are at pains to ringfence who Batman is and try to strictly delineate what the 'real' Batman is like, and what stories 'count', Morrison welcomes all of Bruce's personae into the tent. Even Grant's Invisibles ended up showing us that the good guys and the bad were both on the same side. So Danny's warm inclusivity is very central to Morrison's whole philosophy.

It’s worth stating too, that Jones and Danny are not ideological opposites. Instead, Jones only represents a tiny subset of the huge multivarious world of possibilities that Danny embodies. As at the end of the story, Danny can easily contain Jones little picket-fenced kingdom, but Danny's is by far the larger universe.

Jones acts out of fear and cruelty, whereas Danny is all about love and acceptance. And what does Jones fear? As Danny shows Jones at the end, it's that Mr Jones might actually like the deviancy, and in fact be one of THEM, after all.

An aside: As a practicing magician of a particular sort, Morrison puts a lot of store by coincidences. Consider that ‘reality’ becomes more like fiction when coincidences start to pile up. This is one of the ways his magical theories feed into his work, and contributes to his particular interest in meta-fiction, where fiction and reality intersect.

I snapped up the first Showcase of the 60’s Doom Patrol when it came out a few years ago, and coincidentally (that word again!) I read vol II of Essential Classic X-Men alongside it. (Silver Age stories, despite their charm and craft are often hard to read in bulk!) I say coincidentally, because Classic X-Men vol II contains stories written by Silver Age Doom Patrol co-creator and scribe Arnold Drake. His X-Men stories were a pale shadow of his DP work though.

The second part of the Commander’s look at the original run posited that the comic went downhill, and perhaps lost readers as the Doom Patrol became more accepted heroes within their world and their outsider status became downplayed. In the replies thread I said that I’d comment further once I’d read to the end of the original run. Having recently finished my copy of Showcase Presents The Doom Patrol Vol II, containing the second half of the team’s original run, I thought I’d belatedly add my own thoughts on the Commanders conclusions.

Which thoughts will be the subject of my next post.

"Steele was a race car driver who'd been involved in some sort of horrendous crash. His body was beyond repair but Caulder managed to rescue Steele's brain and rehouse it in a robot body.

Steele, not surprisingly, was less than elated, but what could he do?

"The other guy, Larry Trainor, was an Air Force pilot whose body was occupied by a mysterious 'negative energy' being. This creature had all kinds of strange powers but its presence in Larry's body resulted in him having to be swathed in 'specially treated' bandages to protect others from the radiation he was now emitting. Another happy guy.

"And as for Rita Farr, she was this Hollywood actress who could alter her size without going on a diet.

Regarding Bruno Premiani’s art in all of the 60’s DP appearances, Commander Benson said:

"His early efforts on the Doom Patrol series had that typical European realism, short on conveying motion, but beautiful in layout. His lines were thin---some might say "scratchy"---but tight and full of detail. His figures were realistically proportioned, without the exaggeration common to most super-hero artists."

A lot of what goes on in the 60’s DP is just on the other side of what might be called good taste for a 60’s children’s comic. Check out the attached frames from the second half of the 60’s series for the kind of thing I mean. The hairy chests and shoulders of the deformed mutants drag them a little closer to real than comicbook deformity. What about the way the Guru is holding ‘baby’ Rita in this picture? There’s weird psycho-sexual things going on there!

What about Mallah and the Brain’s final send-off? That’s someone’s real brain cracking out of its casing there! The stories often dwell on the fragility of our bodies and the way we can be estranged from them. I can see why Morrison was able to fit Mallah and the Brain into such an entertaining comic discussion on the mind-body dichotomy in DP #34. Drake and Premiani dwelt unconsciously on these things in the original comics.

"End of story, right?”

Before we get to they extraordinary wrap-up of the original run of Doom Patrol, it's worth looking at Rita Farr's role in the Doom Patrol, which was one factor that made it so affecting. We'll be getting to Rita by way of a look at the team dynamics generally in the second half of the 60's series.

The Commander summed up their appeal thus:

"As a consequence, they stayed sequestered in their brownstone headquarters, where they had only each other for sympathy, friendship, and support. Of all of DC’s hero-teams, the Doom Patrol shared the greatest sense of family. This was something many adolescents could identify with---that feeling of being on the outside, looking in. Much of the popularity of the series derived from this."

I agree with this completely. He notes that as a reader at the time, he felt that the book began to lose something as the Doom Patrol became less anguished about being different and as the introduction of Mento and Beast Boy changed the dynamics of the team.

There may be something in this, as it took me much longer to read to the end of the second Showcase volume than it took to read the first. Perhaps the series did lose something vital after Mento and Beast Boy came along.

Still, I thought that both characters did help broaden out the discussion of what it means to be an outsider, and how the team coped with being ‘on the outside looking in’. This series has something to say about victimhood and how people deal with it. The Doom Patrol were indeed a tightly-knit group, united by their suffering, but Drake kept that very subtextual. If you just went by the dialogue it would seem as if they were constantly getting on each other’s nerves. Negative Man and Robotman, especially, seemed to be always bickering. I think it took the back-up origin stories to show how much they were really suffering and how much they depended on the Doom Patrol to give them a sense of purpose and belonging.

It’s hard not to see that Marvel and DC were keeping an eye on each other when both these contentiously linked books had back-up stories featuring their team members being ostracised as freaks before they joined their respective teams.

Gar Logan was an interesting counterpoint to the rest of the Doom Patrol. Although he was just as much a freak and outsider as Larry and Cliff, he put a very brave face on it, going to school and trying to score dates as if he wasn’t a green shape-changing boy. Drake is very subtle about it, but it looks like Gar was in denial. That might explain why the only green boy in Midway City wore a mask in his superhero identity! Gar is determined to do everything as if he was normal. The Doom Patrol would be a natural place for him, but he keeps insisting he doesn’t need them and his behaviour doesn’t endear him to Cliff and Larry at all.

The psychology underlying how Drake’s characters behave has a certain truth to it. Victims are generally more reactive than passive, and we see Cliff, Larry and Gar all reacting spikily to their lot in life rather than sitting back and let it happen to them.

Thematically, Mento is there precisely because he is relatively normal. I guess Drake wanted to explore how ‘normal’ and ‘different’ interact when they have cause to – the cause in this case being the lovely Rita. The Commander mentions that fans picked up on Rita not needing to be in the Doom Patrol at all. To some extent I think that is her role. It’s not that she is a freak, but that somehow when she became Elasti-Girl, she realised that ‘there but for the grace of God, go I’. She wants to help these brave misfits and to do something more with her life than just be famous for being famous.

Again and again, Rita comes across as being a very evolved, compassionate, thoughtful person, and passionate about doing the right thing. Mento is there as the temptation away from her new philanthropically-inclined life.

She manages, against the odds, to be true to him and to keep doing her good work with the Doom Patrol. Good work in the sense that they save ordinary people from dangerous threats, but also in the sense of being part of something that gives meaning to the lives of her unfortunate friends Cliff and Larry.

Rita’s passion in the pursuit of fairness can be seen in the way she fights to have a life beyond her marriage, which is somewhat ahead of her time, and also in the fire she shows in insisting that Gar doesn’t have to change himself in any way to make society more comfortable with him, and especially not go through dangerous operations on account of society's cruel attitudes towards those that are different.

The final point about Rita ties into the subject of my last post, which looked at the sometimes creepy psycho-sexual areas that Doom Patrol tended to touch on. Basically, the relationship between her, Larry and Cliff is very like that of siblings, except complicated by Larry and Cliff’s obvious attraction to their ‘sister’. Again and again we are told the Doom Patrol is a ‘family’ with the Chief as the Daddy. Part of the DPers objection to Mento’s romancing of Rita is that he is taking her away from the team, but there also seems to be an element of them being jealous of her love for him.

I love how Drake’s Doom Patrol constantly shows us people who love each other while all the time griping at each other. It’s a far cry from the likes of Claremont and Johns who have their characters declare their deepest feelings every time they open their mouths.

Finally, I’d just like to re-state how startling and unprecedented the Doom Patrol’s original send-off was in Doom Patrol # 121, as referenced at the top of the post in the little excerpt from Morrison’s summary. It was shocking in the 1980s when the villain in Black Orchid just goes ahead and kills the heroine a few pages into Gaiman’s mini-series, but Drake had the villains just do it 20 years earlier. “Dead” dead, too, for quite a while.

Having said all I have about lovely Rita Farr, I’m glad that they kept her dead for so long. She was beautifully handled by Drake, and it was fitting that someone of her moral calibre made the true sacrifice that is rarely seen in superhero comics, even though, given the chances superheroes take, and the ruthless villains they oppose, her fate should be much more common.

.

Just found this thread as I happen to be re-reading the trades.

I never read any of the original DP and am intrigued enough to put them on my mental to get list.

I love Morrisons version though,wonderfully weird without crossing over to stupid or just weird for weirds sake.Mr Nobody soon became my favourite villain and there are loads of tiny things which make the series great,just something like Cliff insisting on calling Rebis,Larry just a small thing but I like it.

...I believe that , when the original death of the Silver DP happened , the editors/whoever specifically said " Will the DP ever come back ? Only YOU , the readers can decide that ! " , i.e. , they did have - or would have found ! - some way to reverse if if the response/whatever had been strong enough .

Remember , 1968 was a year when DC culled its super-hero titles unmercifully , just in DP's case for whatever reason all concerned weree allowed to prepare a sendoff...Did anyone ever ask Drake - or Boltinoff - what they had had in mind , if there had been a 180() turnaround ?

Also, just like Morrison's, the dialogue continually amuses. Both versions of the DP capture the spiky and sarcastic way these teammates/support group interract. It's very hard to get that across in these reviews.

Anyway, glad you're reading along, and that this little diversion from Morrison's run was of interest to you.

Emer, the final issue of Drake's DP is pretty unique in SA DC. Not only did it end the series on a full stop, (a real rarity) but it alllowed DC to take the series up again should there be enough interest.

I didn't say too much about the publishing context. Apparently Drake and DC had parted ways just before this final issue, but Drake scripted #121 as a favour to Premiani (I think). Was this Drake's last work for DC? Maybe they still had stand-by stories of his on file that they published later?

Does Drake's leaving DP/DC directly coincide with the older creators asking for benefits and pensions and being sacked?

Figserello said: